For a long time I thought I knew about accessibility and inclusion. But like for many subjects, once you start learning, you realised there is a lot more to it.

We still often stay at the surface on these subjects. This blog post will try to show other layers so people can realise quicker that they need to dig deeper.

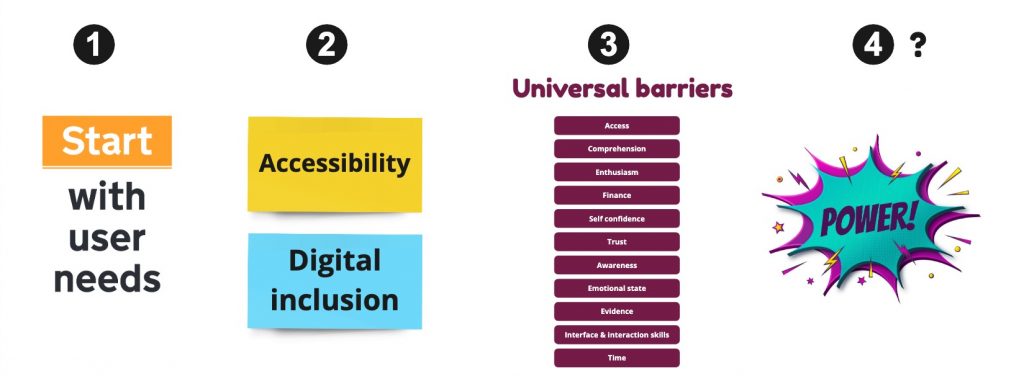

How it (should) work in government

Start with the user needs

The first government design principles is “start with the user needs”:

Service design starts with identifying user needs. If you don’t know what the user needs are, you won’t build the right thing. Do research, analyse data, talk to users. Don’t make assumptions. Have empathy for users, and remember that what they ask for isn’t always what they need.

In government, we still have to advocate for this sometimes outside a project team. With the operations teams for example or with some senior stakeholders who are not familiar with this way of working.

Users needs are not always well articulated, and we might not have gone far enough to look at the root cause of the need. It also often ignores the context of the user.

We don’t always look at all the users. Some groups might not be identified or prioritised. Like people supporting applicants for example.

Accessibility and digital inclusion

Even though the description of point 5 mentions: “avoid excluding any groups within the audience they’re intended to serve”, we usually only look at:

- digital accessibility… and forget that it could be about physical accessibility as digital teams (and their stakeholders!) focus mostly on the online service and often ignore parts of the service which are not online

- digital inclusion = looking at people who might not have access to internet, or the skills or confidence to use it… but we sometime forget that people might only have a phone, or very little data, or a poor network

- external users… we often do not address or prioritise the accessibility of internal users who are providing the service and we assume that they have good digital skills which is actually not a given

Universal barriers

I first heard of this framework in 2022 during the ‘service week’ – an event for civil servants only. Some project teams are using it in various government departments, but it’s not well known and rarely used.

The Universal Barriers framework lists 11 barriers that are universal to all people and applicable to all situations. It encompasses barriers more likely to be experienced by vulnerable groups — for example, people with disabilities, nowhere to live, or low literacy — while remaining open to inclusion for someone who is fully able, with high digital skills and high levels of literacy.

Ben Carpenter – A framework for full inclusion

I wrote about it: Removing barriers to inclusion, and tried to promote this in various conferences and work places since 2022.

I’m not going to quote myself 😉 , you can read my blog post about it. The idea is that we need to look at the context of our users and their ‘state of mind’. They might be in a vulnerable situation when using our service and we should think about these situations to ensure that our design do not exclude people.

Power

The universal barriers can help project teams look at different sort of exclusions. They are not set in stone, and can be adapted to your service.

But some aspects can still be missed, like cultural differences, or if your service is asking about sex or gender; you might encounter a lot of resistance to look further than Male and Female as the only options. On this, you can read: Let’s talk about sex by Emma Parnell, or Sex and/or gender — working together to get the question right by Jane Reid.

As a designer, if you are the only person advocating for this, it can be exhausting. If you have already been pushing for the user needs, the accessibility of the service for both external and internal users, the digital inclusion, maybe even looked at some universal barriers, then you might not have a lot of energy left to go further.

I think the problem remains that most people involved in creating services are still often unaware of their privileges and biases. Researching with various users helps, but unless we make the effort to educate ourselves, we will keep excluding some users because we do not understand their experience as it’s too far from ours. Even when you understand it, you might have no energy left to convince others in your project team that it’s important.

If you want to learn more about power, I’ve gathered resources to understand power in design.

Trauma

I’ve learned about trauma informed approaches in the last two years. I’m no expert. We talk about it more and more but it’s another area where many do not realise the impact it has on people. If you want to learn more, this article by Kate Every is a good start: Why trauma-informed approaches are vital to design and research. Edit 17/01/25: longer read, but the book Designed with Care covers many aspects.

One example: problems with letters

Many government services are still heavily paper-based. We send letters to people, assuming they will receive it, open it, and know how to read it. It’s a lot of assumptions!

Unfortunately, the post is not as reliable as it used to be, we might have the wrong address for them or an abusive partner might be controlling their mail.

For people who have been living in poverty, receiving a letter can be triggering. Letter are rarely good news for them. It might be hard to open any ‘administrative-looking’ letter, or in fact, any letter. This can last years after their situation has improved. Jack Monroe explains this well in “Poverty has left me unable to open my own front door“.

Or this quote from a blog post:

The pile of post sitting in the hallway, unopened for months on end, because letters always meant bad things. Brown envelopes especially; I found some from 2013 last week that are still sealed […] that brings its own headaches, penalties, mental clutter, paranoia, and acute feelings of failure as a parent, as an adult, as the head of a household, as a human being – Jack Monroe

Even if they do open them, people might not be able to read or make sense of them. The content might be too jargony, or sounds like a threat.

I still remember, while working to transform a service, one civil servant from the team delivering that service saying: “they are guilty of not reading [the letters we send them], that’s why they are in this situation”. The person was referring to people who were in debt. They had clearly no idea that the content of these letters were actually way too complex to read, too long, and some of the people receiving these had left school without learning how to read.

When people think ‘they know’

I’ve done some usability testing recently, and was reminded of a behaviour where if people think they understood the question being asked on a screen, then they are unlikely to check any additional guidance you provide under that question. The guidance will only be useful to someone who is unsure and looking for help.

I think it’s a similar issue we have with accessibility and inclusion, if people think they know about it, they won’t try to learn more.

I’ve worked with many people who thought they knew about accessibility. In fact, they had a very shallow knowledge of it. Online, they think it’s about enabling blind users who do not see at all to use a screen reader, and in the physical world, it’s about people in a wheelchair who do not walk at all. They don’t know about all the nuances a condition/impairment can have and many are completely unaware of invisible disabilities.

People sometimes think they know because they trust others who seem to know what they are doing. It’s important to have different opinions, ideally from disabled people who can share their experience with you, and to challenge ‘best’ practices. I’m giving two examples below, but there are a lot more misconceptions. I’ve written about this: Avoiding misconceptions on your accessibility learning journey

Accessibility overlays

Recently, I got in touch with a designer who thought that providing websites with an accessibility overlay was the right thing to do to make websites accessible. I remember the first time I saw such a menu for accessibility, I thought: “oh it’s nice, they are thinking about accessibility”… I was at an early stage of my journey to learn about accessibility.

Now that I know better, I realise that, not only does it not help, but it actually often makes things worse…. But these overlays are produced by people who are supposed to be ‘accessibility experts’ so when people do not know too much, it’s tempting to trust experts, and dismiss advice from ‘lone accessibility advocates’.

To learn more about overlays and why you should not use them: Overlay Fact Sheet

Giving a visual description of yourself

Many people think it’s more inclusive to people with visual impairments to give a visual description of themselves before speaking in conferences, online or face to face. It’s sometime encouraged by organisers, thinking this is good practice to be more inclusive for people who cannot see the speaker. The idea behind this I guess, is assuming that people are missing out because they are curious about what you look like, what you wear etc… I’ve always been puzzled by this, because when I listen to a podcast, I don’t see the people speaking and personally, I’m not curious about what they look like. The results of a survey from Karen McCall who has a visual disability show that this practice is unhelpful and even disliked by a majority of people with visual disabilities

You just need provide relevant context that could be missed if not stated in your visual description: think of what might make a person consider you differently as a speaker if they could see you.

When I speak at a conference and give info about me, I say I’m a white woman in my ’50s. In most cases, this is enough context. People do not need to know about my hairstyle, the colour of my glasses, or what I’m wearing.

How we understand the world we live in

We all have mental models which will influence how we understand the world and make decisions.

A mental model is an internal representation of external reality: that is, a way of representing reality within one’s mind. Such models are hypothesised to play a major role in cognition, reasoning and decision-making.

If you are privileged you often have no ideas of the difficulties others are facing. Until you really listen to people, or some of these privileges are taken from you.

Cultural differences

I used to live in Paris. I was teaching young children at the time. In the school and neighbourhood I was working in, the families were coming from very diverse cultures.

At the time, I did some volunteering to teach French as a foreign language to adults. Some had been in France for a long time, but had never learn to read or write French. They could speak it though. All of them were speaking at least another language but some of them had never learn to read and write in their mother tongue. When I asked them what would be useful to them, some wanted to read food packaging for their recipes or read appointment cards from the GP.

Until then, I had never realised that an appointment at 14:15 might make no sense to someone who had never used the 24-hour clock system. Or that people might not know that streets in France have odd numbers on one side of the road and even numbers on the other side. Or that ‘1L’ on a bottle of milk means one litre and ‘Kg’ is kilogramme. I used to take all this for granted as it didn’t feel like something I ever had to learn.

My own experience

When I eventually moved to Scotland with my family, I started to understand even better some difficulties the parents of the children in my class were experiencing back in France.

The way a school day worked was different from France so I was relying on my young kids at the time to tell me what had happen at school. I did ask the teachers too, but sometimes, you feel a bit stupid asking basic things that everyone else seems to know.

Speaking over the phone was more stressful, I wasn’t sure I had understood the person on the line. I was now struggling to spell my email address or to write down an address someone was giving me.

Numbers were harder to process for me as my brain does the little gymnastic of translating them in French which slows me down.

All the medical information at the GP was named slightly differently, the name of the vaccines were different, for example what I knew as ROR was now MMR, or ‘angina’ in English was much more severe than what I knew as ‘angine’ in French (= soar throat).

Everything makes you a bit more unsettled and disempower you. I should add that I was still very privileged as people were really nice and patient with me which is not always how people are treated in that scenario.

Be proactive

I’ve written many times already about how to learn about accessibility. Following disabled people on social media is a good way to do this. That’s how I’ve learned a lot myself. But now, I feel a bit bad telling people to learn via social media when I’ve left many of these spaces myself. Blog posts or newsletters might be a good alternative. You can do the same about inclusion really. I can give some starting points and you can see who they signpost you to, depending on your learning interests:

- Ettie Bailey-King – Fighting talk

- Craig Abbot

- Anti-Racism Reading List August 2024

- Human library